The Nature Conservancy Discovers Evidence of Two Bird Species Returning to Palmyra Atoll

The Nature Conservancy was using RAIC to measure the seabird population on Palmyra Atoll. They found two species that hadn’t been observed there in decades.

- The Nature Conservancy, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Island Conservation have worked to restore seabird habitats in order to reattract eight seabird species that have been believed locally extinct from Palmyra for decades.

- The observations of the blue noddy and wedge-tailed shearwater are a validation of their efforts, and a positive sign for the health of the ecosystem.

- The discovery came as a result of TNC’s innovative use of drone monitoring and AI analysis.

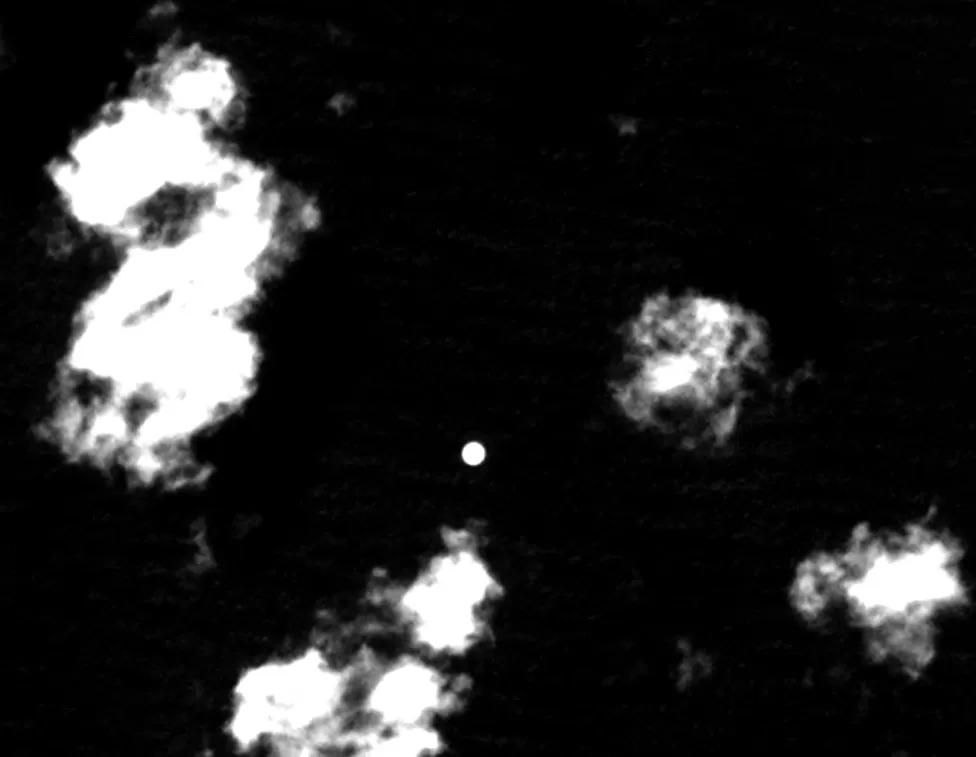

Nesting Wedge-Tailed Shearwater Birds

One of these birds is not like the others.

To say that Alex Wegmann, Island Resilience Lead Scientist at The Nature Conservancy (TNC), is familiar with the birds of Palmyra Atoll would be an understatement. “If a bird flies by me, I can tell you what it is by the sound it makes, or the way the wings are flapping,” he said. “It’s kind of second nature.”

That’s why, late one night, as Alex was using Synthetaic’s Rapid Automatic Image Categorization (RAIC) to pore over drone imagery of Palmyra, a bird whose dark plumage and profile didn’t match the others immediately jumped out at him.

It was a wedge-tailed shearwater — one of eight seabird species believed to have been extirpated (or locally eliminated) from the island during World War II, when rats, cats, and other non-native life were introduced, wiping out ground-nesting seabirds.

It was just one sighting, but Alex knew it pointed to something bigger: “This couldn’t be a chance occurrence. What’s the probability that we captured the one time a wedge-tailed shearwater flew over the lagoon?” The single image of a single bird was a validation of a years-long, ongoing effort by The Nature Conservancy to restore seabird populations on the Palmyra Atoll — work with ripple effects across an entire ecosystem, and which may have implications in ecosystems all over the world. “It was a massive confirmation that our efforts are worth it. That we’re not on a fool’s errand.”

The Palmyra Atoll Rainforest and Relief Resilience Project

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) is a global environmental nonprofit doing innovative conservation work in over 70 countries. Guided by a vision of “a world where the diversity of life thrives, and people act to conserve nature for its own sake,” TNC brings decades of experience to its current priorities of the dual crises of climate change and biodiversity loss.

TNC purchased Palmyra Atoll in 2000 and shortly thereafter sold much of it to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). Today, TNC and USFWS co-manage the atoll as a TNC nature preserve that includes a research station. This management scenario creates a unique partnership and incredible conservation opportunities. Palmyra holds both practical and symbolic significance to TNC’s goals. It inspired the establishment of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument,a protected area that the USFWS calls “one of the last frontiers of scientific discovery in the world and… a safe haven for Central Pacific biodiversity.” Research conducted at Palmyra has international significance and has yielded valuable knowledge about ecosystem recovery and coral reef resilience.

When intact, atolls are dynamic and resilient ecosystems, capable of adapting and reorganizing in response to changing ocean conditions. It’s believed that when coconut palms and rats were introduced to the atoll prior to and during World War II respectively, the delicate balance of the atoll’s ecosystem began to crumble. The rats, lacking natural predators, wrought havoc on the native flora and fauna. Coconut trees, planted as a cash crop, went on to make up nearly half of the forest canopy, their roots forming thick and knotted masses on the forest floor.

TNC has made significant process reversing these human-caused impacts to the atoll. Rats were eradicated in 2011, and the abandoned coconut palm plantation has been significantly reduced, making way for native trees to grow back. The process gives nesting and roosting places back to seabirds — where much of the project’s focus lies today.

Atoll conservation: It’s for the birds.

Like a cornerstone knocked loose, seabirds are pivotal to the health of their ecosystems, but have been displaced from much of their original habitats at Palmyra. Eight species of seabird that are known to the region are not found on the atoll today.

Explaining the importance of these species, Katie Franklin, Island Conservation Strategy Lead for the Palmyra Program at TNC, said: “Studies at Palmyra, Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean, and elsewhere indicate the valuable role of nutrients in seabird guano for maintaining atoll ecosystem resilience to the impacts of climate change.”

Now that their habitats have been restored, TNC is actively trying to attract the eight seabird species back to Palmyra. Methods include playing the calls of all eight species on a loop and creating decoy colonies of plastic replica Blue Noddies and Grey-backed Terns. Earlier this year, a grey-backed tern chick was seen, confirming the success of these attraction methods.

The Palmyra project team refers to a “partnership” with the seabirds. Katie said: “Through management actions that provide them more nesting and roosting habitat, we’re allowing them to support the entire terrestrial and marine ecosystem with the beneficial nutrients in their guano.” In an example of what’s known as biotic connectivity, the presence of seabirds is known to enhance productivity and functioning of adjacent coral reef systems.

All that explains why Alex found himself jumping up and down when RAIC surfaced an image of a wedge-tailed shearwater, one of the eight species believed extirpated, in its automated analysis of drone photos taken over the atoll.

Much like the seabirds of Palmyra have significance far beyond the confines of their nests, that moment of discovery has exciting implications for the use of technology in conservation efforts around the globe. That’s because it came as a result of TNC’s innovative approach to answering the question, “How many seabirds are on the atoll?”

How to Conduct a Seabird Census

Perhaps the greatest challenge of the seabird habitat restoration program has been measuring its success. When TNC got started, no one had accurate estimates for how many seabirds there were on the atoll — an essential piece of data for understanding the program’s progress. Obtaining a count via direct ground observation was not an ideal solution. For one, much of the atoll is difficult to access safely, especially without disturbing the environment. “Humans are great at causing impact, even when we’re trying hard not to,” Alex explains. “Our very presence is a disturbance, despite a lot of mitigating effort. Anything that can be done to reduce the number of people in the ecosystem and the amount of time we’re spending there, without reducing the quantity and quality of data, is a positive.”

TNC set out to do just that, launching a drone program in 2020. They’ve since captured terabytes of imagery.

Still, there was no standardized method or bespoke model for counting birds in the drone photos. That is, they could collect the data, but had no way of analyzing it at scale. A team of researchers at the University of Florida would, in 2022, develop a “generalized deep learning model for bird detection.” The model didn’t meet TNC’s specific needs at Palmyra, but Alex said, “It gave us the confidence that this was possible, and that we could find a way to do it even better.”

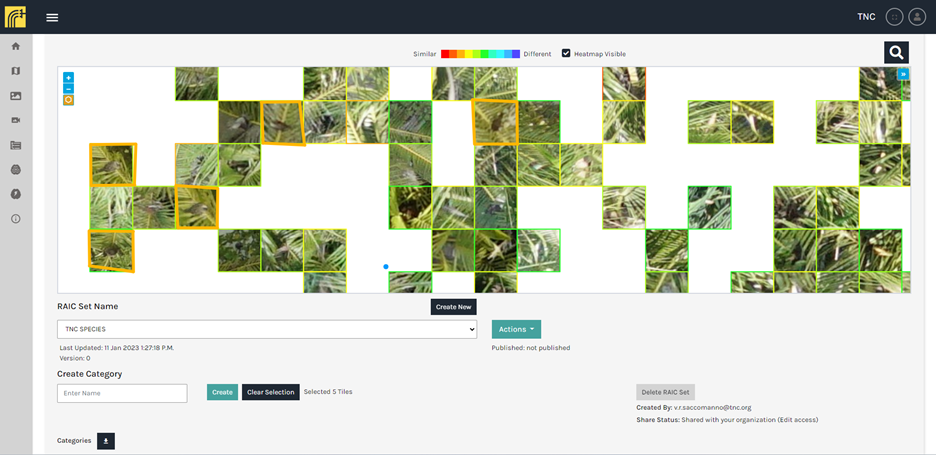

That’s where RAIC came in. RAIC is a tool for analyzing large, unstructured visual datasets. Powered by an unsupervised AI, RAIC allows anyone to obtain insights from visual data, without needing to expend major time and labor labeling that data. It’s proven invaluable to The Nature Conservancy in analyzing terabytes of drone video and images taken over Palmyra.

RAIC: Less time looking for answers, more time finding them

By eliminating the need for labeled data, RAIC changes everything you thought you knew about detection AI.

“We’re blown away by the model we were able to create in RAIC,” said Alex. “It is making it possible to, for the first time, answer the question, ‘How many seabirds are at Palmyra?’.”

“Data from aerial drone surveys and AI analyses allow us to reliably quantify changes in seabird abundances, habitat use, and marine-derived nutrient input,” said Katie. “These types of analyses open doors for understanding the ecosystem response to our management action on a large scale over time and have implications for enhancing climate resilience in island ecosystems globally.”

TNC’s most thrilling detections in RAIC so far — a wedge-tailed shearwater and a blue noddy, both among the eight species thought extirpated — were, to some extent, an unexpected bonus. Alex said: “We would never ever have found either of those birds looking at the image data on our own. There was too much data, the imagery was too complex, and the birds didn’t fit the profile of what we were looking for. But analyzing our data in RAIC, those results suddenly became accessible in a way they wouldn’t have been otherwise.”

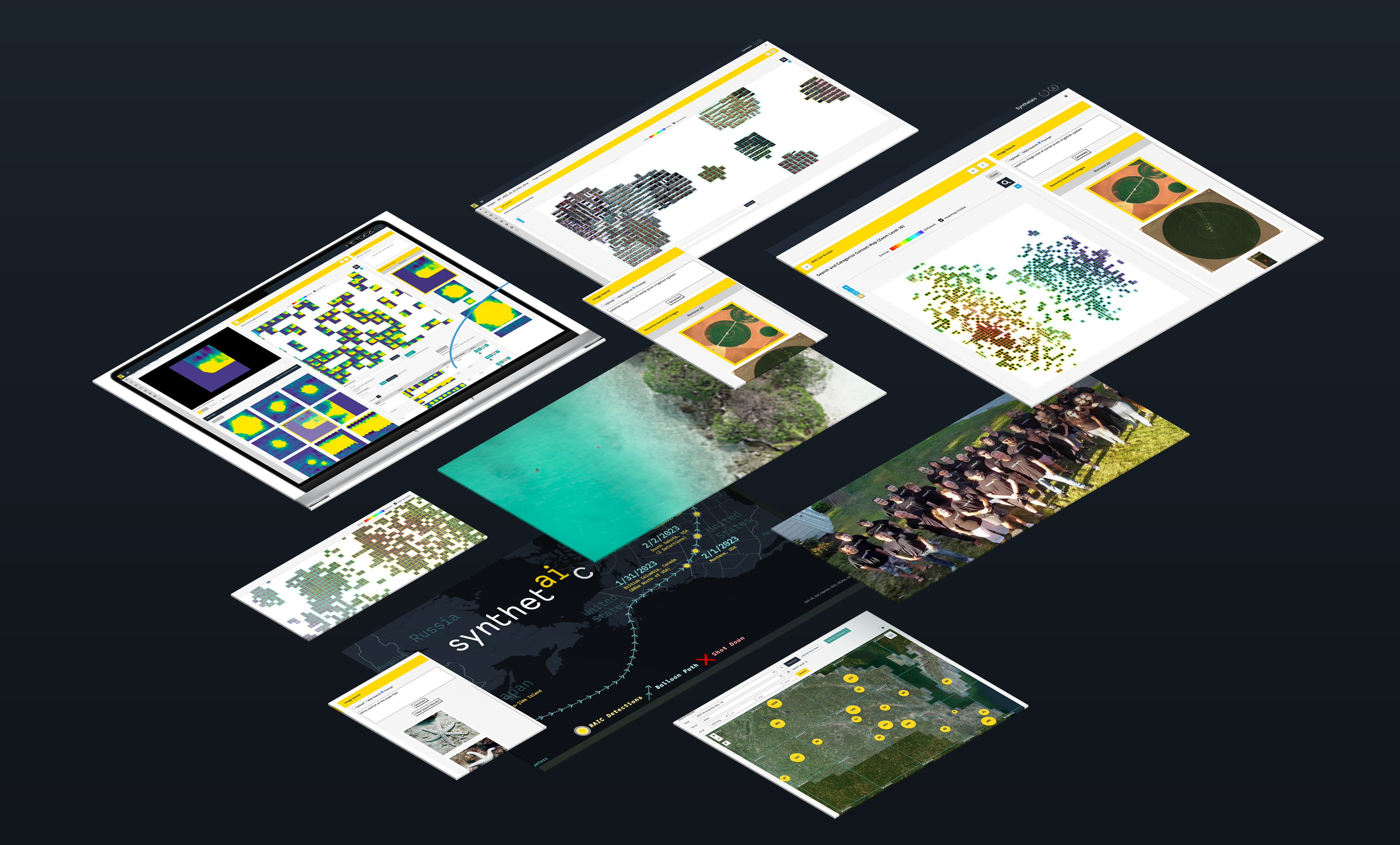

Screenshot of RAIC search results for Great Frigatebirds in coconut palm crowns

(“Accessible” may not even be a strong enough word: Alex said his six-year-old daughter loved “playing” with RAIC, clicking through search results and running searches of her own, like the Palmyra imagery were an I Spy book.)

RAIC detected blue noddies roosting on palm fronds, where humans wouldn’t have looked. Blue noddies are known to typically nest in small colonies on the ground, or, if any are available, on cliffs. Alex had seen blue noddies in coconut palm crowns once before: on nearby Tearania (Washington) Island, Kiribati, all the way back in 2005, and it struck him as unusual at the time. When RAIC surfaced the image, he was reminded of that previous encounter: “If blue noddies are coming to Palmyra from Tearania, and they’ve already associated palm trees with usable habitat, why wouldn’t they be up in the palm crowns at Palmyra?”

"I guarantee you we would not have found either of these species in the imagery without RAIC."

With a wealth of drone imagery and the search capabilities of RAIC, TNC researchers won’t have to look at every palm crown across the atoll for blue noddies; they can simply feed the result to RAIC to find more of the birds across future datasets.

What’s the next frontier for TNC and RAIC?

The Nature Conservancy’s work at Palmyra is ongoing; so is their exploration of technology to scale their work. Now that they’ve created a process for detecting and counting birds on the atoll, the next major step is to incorporate geospatial data. That is, they plan to move from “How many birds are there on the atoll?” to “Where are the birds on the atoll?”

From there, it will be crucial to measure the seabird response over time to TNC’s management actions. How will the seabird community grow and change? What will it look like in 5, 10, or 15 years? Through their drone imagery analysis program, they’ll now be able to measure this change.

Finally, Palmyra is just one atoll. “We hope to demonstrate how creating ‘seabird forests’ can be a natural climate adaptation management approach that can be replicated on other low-lying atolls and islands throughout Oceania with declining or absent seabird communities,” said Katie.

The next locale that may take on the management actions and measurement toolkit developed at Palmyra is Tetiaroa Atoll, home to the Brando Resort, in French Polynesia. The atoll is the subject of an ongoing conservation effort by The Tetiaroa Society, Island Conservation, and others.

TNC is hopeful that their learnings will be valuable to the efforts at Tetiaroa, and believes that the ecosystems and bird species between the two atolls are similar enough that equally valid results can be achieved in RAIC. Alex said, “I strongly believe that what we’re doing at Palmyra is scalable and repeatable.”

It helps that RAIC’s search capabilities are totally object-agnostic: where detection AI has historically relied on bespoke models, RAIC uses mathematics to understand the data domain. It could just as easily search drone footage (or satellite imagery, which RAIC is also adept with) for any other object of interest. Alex offered one possibility for atoll research: “In terms of ecosystem function, land crabs could be the next seabirds.”

Land crabs — the next seabirds?